A few months back, when the Lavender Caucus was seeking co-sponsors for its complaint before the Accreditation Committee seeking to revoke the accreditation of the Georgia Green Party, the question came before the Illinois Party. Rich Whitney, an attorney, past Green Party nominee for Governor of Illinois (who took 10% of the state-wide vote) and current chairman of the Illinois party, opposed his state party's becoming embroiled in the controversy. What follows was written by Rich Whitney who prepared it for circulation among the state committee in Illinois. Today he released his brief on the subject for circulation before the National Committee.

-

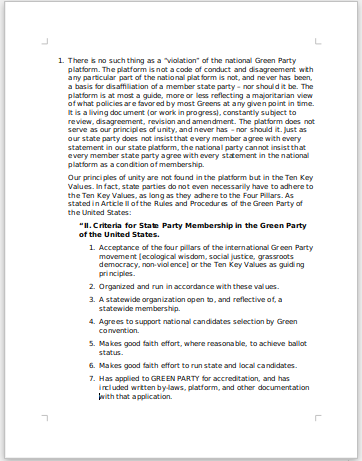

There is no such thing as a “violation” of the national Green Party platform. The platform is not a code of conduct and disagreement with any particular part of the national platform is not, and never has been, a basis for disaffiliation of a member state party – nor should it be. The platform is at most a guide, more or less reflecting a majoritarian view of what policies are favored by most Greens at any given point in time. It is a living document (or work in progress), constantly subject to review, disagreement, revision and amendment. The platform does not serve as our principles of unity, and never has – nor should it. Just as our state party does not insist that every member agree with every statement in our state platform, the national party cannot insist that every member state party agree with every statement in the national platform as a condition of membership.

Our principles of unity are not found in the platform but in the Ten Key Values. In fact, state parties do not even necessarily have to adhere to the Ten Key Values, as long as they adhere to the Four Pillars. As stated in Article II of the Rules and Procedures of the Green Party of the United States:

“II. Criteria for State Party Membership in the Green Party of the United States.

-

Acceptance of the four pillars of the international Green Party movement [ecological wisdom, social justice, grassroots democracy, non-violence] or the Ten Key Values as guiding principles.

-

Organized and run in accordance with these values.

-

A statewide organization open to, and reflective of, a statewide membership.

-

Agrees to support national candidates selection by Green convention.

-

Makes good faith effort, where reasonable, to achieve ballot status.

-

Makes good faith effort to run state and local candidates.

-

Has applied to GREEN PARTY for accreditation, and has included written by-laws, platform, and other documentation with that application.

-

Has a history of networking with other environmental and social justice organizations.

-

Evidence of commitment to, and good faith efforts to achieve, gender balance in party leadership and representation.

-

Evidence of good faith efforts to empower individuals and groups from oppressed communities, through, for example, leadership responsibilities, identity caucuses and alliances with community-based organizations, and endorsements of issues and policies.”

Agreement with the national party platform, let alone every provision of the platform, is not on the list of criteria. If there are grounds for suspending or terminating the affiliation of the Georgia Green Party, they must be based on one or more of these criteria, not disagreement or conflict with the national platform.

Indeed, it would set a terrible precedent to base either suspension or disaffiliation of a member party based on the national platform. For example, the national party recently voted down a proposed platform amendment (proposal 1005) that called for recognizing legal “personhood” to natural eco-systems (basically adopting the position of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund) and designating at least 50% of the planet as a nature reserve. If a state party were to adopt such a position in its own platform, or publicly express support for such a proposal, would the national party then be justified in suspending or expelling that state party as well?

The current platform contains any number of provisions about which Greens disagree. For example, one provision calls for making “airports accessible by local transit systems.” A state party might take a position that we should instead be closing down more airports and greatly limiting air travel based on its disproportionate contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. Would we then be justified in disaffiliating that state party for taking a position in “violation” of our platform?

More broadly, we know that many Greens disagree about the best policies for sex workers or monetary reform, whether or not we should identify as eco-socialist, whether we should support more proactive population control measures, whether we should support a national health service as opposed to single-payer health insurance – and numerous other questions. Do we really want to establish a precedent allowing the national party to disaffiliate any state party that takes a position at variance with the national platform?

If the national party sets a precedent of suspending or removing state parties based on disagreements or conflicts with the national platform, we could turn our national party into a circular firing squad. Policy disagreements, or disagreements with the national platform, are not a proper basis for attacking the affiliation of a member state party.

-

It is not until the very last paragraph of point 7 of the Complaint that it briefly references the correct criteria, as an aside. It simply makes a few conclusory statements that the Georgia Green Party’s platform changes violate the pillar of social justice; that the party is not open to, and reflective of, a statewide membership, and it has failed to make good faith efforts to empower individuals and groups. However, the Complaint merely asserts its conclusions, with no analysis provided.

Whatever flaws may exist in the Georgia Green Party’s analysis, its amendments are clearly motivated by a desire to protect women’s human rights, and, therefore, social justice. The fact that many of us would disagree with their interpretation of social justice does not show lack of “acceptance” of that pillar by the GAGP.

The fact that it adopted these amendments also does not demonstrate that it has failed to be “open to, and reflective of, a statewide membership.” That criterion is vague but it appears to mean that the party’s decisions should be reflective of the views of its membership. In other words, it goes to the process used to modify the platform and whether it was democratic. We have no information provided as to whether it was or was not reflective of the statewide membership of Georgia Greens (although it was adopted at a state meeting, thereby creating a presumption that it was); therefore, there is no basis upon which to charge the GAGP of having failed to satisfy that criterion.

There is also nothing in the Complaint that would show that the GAGP cannot present any “[e]vidence of good faith efforts to empower individuals and groups from oppressed communities.” Even if, in this instance, one were to conclude that its platform amendments were misguided or poorly reasoned, that would not necessarily prove bad faith, let alone vanquish its prior evidence and history of good faith efforts to empower individuals and groups from oppressed communities.

In short, the Complaint fails to demonstrate that the GAGP no longer satisfies the criteria for affiliation with the GPUS. It offers a critique of the GAGP’s platform amendments, but that is not a proper organizational basis for suspending or terminating affiliation.

-

The contention that the GAGP “is in violation of Federal Law,” based on the Supreme Court’s opinion in Bostock v. Clayton County, is simply flat wrong. Bostock was an important victory for the rights of trans-persons because it recognized that Title VII bars employers (with 50 or more employees) from discriminating against employees based on their transgender (as well as sexual preference) status. Unless there is some evidence that the GAGP employs more than 50 people and failed to hire, fire, or otherwise committed an adverse employment action against a trans-person, it did not violate Bostock or Title VII. Thankfully, neither Bostock nor any other federal law bars political parties, associations, or anyone else from advocating for policy changes, which is protected First Amendment activity.

-

In general, I would object to suspension or disaffiliation of a state party based on its drawing a conclusion about how our values translate into concrete policies that differ from the conclusions drawn by another member entity, in this case a caucus. I would especially object to taking such a drastic step without allowing the affected state party to explain its position or the basis for it. We haven’t heard the Georgia Green Party’s side of this dispute except for the quotation of the amendments that have been critiqued. Those amendments make very specific factual allegations, most of which are not specifically answered in the Complaint. It would be helpful to know the source materials and bases of these allegations, so that they can be assessed, tested, refuted or verified, etc.

In other words, what this circumstance calls for is not summary suspension after hearing only one side of a disagreement, but an open political discussion, with all sides (and I submit that there are more than two) able to present their arguments about what policies best advance Green values, and the factual bases for them. Summary suspension without dialogue and free, civil discussion and debate is not in keeping with our pillar of grassroots democracy.

In this, I agree with the sentiment expressed by our Black Caucus:

“We value discourse and reflective inquiry to resolve conflicts and the many pressing issues in our society today. As such we do not, yet, support expulsion of any affiliated state or caucus, on the issues of languaging around Women’s rights, Children’s rights, and Transperson’s rights. We are stating without reservation all of these are human rights and need to be take seriously. To this end we are aware that there are issues on many sides of these issues that need to have serious consideration. We are talking about real people with real issues and their concerns cannot be taken lightly.”

To be clear, I personally support the rights of transpersons to be fully accepted and to participate fully in society, and to express themselves as they choose, without being subjected to invidious discrimination, and, as I indicated last March, I do not support the GAGP’s amendments. But rights do have limits and contours. The right to free speech does not include the right to drive around in a sound truck with amplified speech at 3 o’clock in the morning. The right to bear arms does not include the right to bear a rocket launcher. Rights also must be defined in a way that do not transgress the rights of others – and these are not always simple questions with simple answers.

Should anyone who self-declares themself to be female, without any verification or basis for the claim beyond that declaration, be admitted into women’s spaces? I can tell you that many women are uncomfortable with that proposition. Last Fall, at the global Climate Convergence held in Southern Illinois, a caucus of Native American women from across the nation made a point of critiquing the genderless bathroom signs put up by the organizers, stating that, as a frequent target of sexual predators, they did not appreciate that decision. I thought that they were overreacting, but I’m not a Native American woman with that lived experience. Obviously, many women disagree with the notion that they need such protection – but isn’t that a reason to get all of the facts and hear all points of view?

The other concerns underlying the Georgia GP amendments appear to be based on protecting children who identify as trans from the potentially harmful consequences of puberty blockers and other medical interventions before they reach an age at which their consent can be fully deemed informed, and the practice of letting persons born with XY chromosomes compete in women’s sports. With respect to the former, I’m not sure what the best answer is, but I don’t think that just citing to the Standards of Care adopted by one professional group settles the question. Professional associations – like any branch of science under capitalism – can be corrupted by the presence of money, and here we have the profiteering of Big Pharma and the medical-industrial complex looming in the background. This is exactly why we need to get all of the facts on the table and have a real discussion.

Regarding trans-woman participation in sports, it would appear that taking testosterone-suppressing chemicals and female hormones do not fully eliminate the advantages of growing up with that Y chromosome. Renowned left/LGBT journalist Glen Greenwald recently wrote about this at The Intercept, noting the mob-like hatred directed at lesbian tennis icon Martina Navratilova in opposing trans-women’s participation in female sports, despite her support for trans-women’s rights generally. Again, citing to Greenwald and Navratilova does not prove that their perspective is one that the Green Party should adopt, but it does provide additional reason for us to have an open political discussion about this – and not a rush to judgment during a campaign.

For all of the above reasons, I have concerns about this proposal and oppose its adoption.